Subtitles & vocabulary

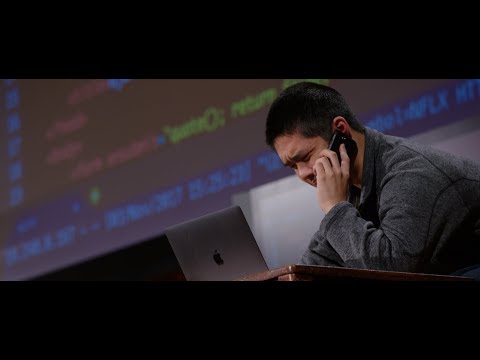

CS50 2017 - Lecture 11 - JavaScript

00

小克 posted on 2017/11/14Save

Video vocabulary

literally

US /ˈlɪtərəli/

・

UK

- Adverb

- In a literal manner or sense; exactly as stated.

- Used for emphasis to describe something that is actually true, often to highlight surprise or intensity.

B1

More audience

US /ˈɔdiəns/

・

UK /ˈɔ:diəns/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Group of people attending a play, movie etc.

A2TOEIC

More script

US /skrɪpt/

・

UK /skrɪpt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Written text of a book, play, film, or speech

- Set of letters or characters of a written language

- Transitive Verb

- To write a text for a movie, play or speech

B1

More feature

US /ˈfitʃɚ/

・

UK /'fi:tʃə(r)/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Special report in a magazine or paper

- Distinctive or important point of something

- Transitive Verb

- To highlight or give special importance to

- To give prominence to; to present or promote as a special or important item.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters