Subtitles & vocabulary

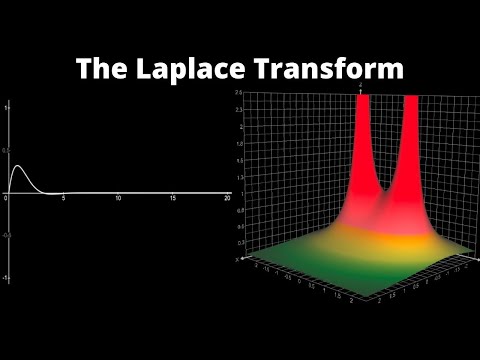

What does the Laplace Transform really tell us? A visual explanation (plus applications)

00

Sujuku posted on 2022/11/16Save

Video vocabulary

entire

US /ɛnˈtaɪr/

・

UK /ɪn'taɪə(r)/

- Adjective

- Complete or full; with no part left out; whole

- Undivided; not shared or distributed.

A2TOEIC

More essentially

US /ɪˈsenʃəli/

・

UK /ɪˈsenʃəli/

- Adverb

- Basically; (said when stating the basic facts)

- Used to emphasize the basic truth or fact of a situation.

A2

More assume

US /əˈsum/

・

UK /ə'sju:m/

- Transitive Verb

- To act in a false manner to mislead others

- To believe, based on the evidence; suppose

A2TOEIC

More eventually

US /ɪˈvɛntʃuəli/

・

UK /ɪˈventʃuəli/

- Adverb

- After a long time; after many attempts; in the end

- At some later time; in the future

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters