Subtitles & vocabulary

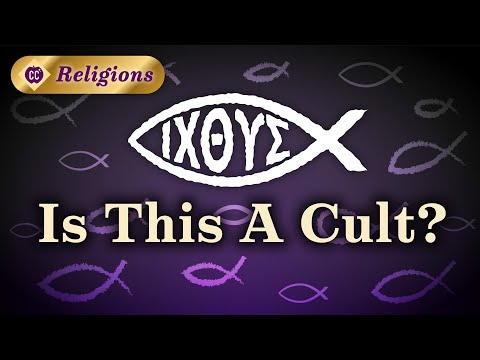

What's the Difference Between Cults and Religion?: Crash Course Religions #3

00

Jack posted on 2024/10/10Save

Video vocabulary

weird

US /wɪrd/

・

UK /wɪəd/

- Adjective

- Odd or unusual; surprising; strange

- Eerily strange or disturbing.

B1

More eventually

US /ɪˈvɛntʃuəli/

・

UK /ɪˈventʃuəli/

- Adverb

- After a long time; after many attempts; in the end

- At some later time; in the future

A2

More dedicated

US /ˈdɛdɪˌketɪd/

・

UK /'dedɪkeɪtɪd/

- Transitive Verb

- To state a person's name in book, song, in respect

- To give your energy, time, etc. completely

- Adjective

- Devoted to a task or purpose; having single-minded loyalty or integrity.

- Designed for or devoted to a specific purpose or task.

B1

More associate

US /əˈsoʊʃiˌeɪt/

・

UK /ə'səʊʃɪeɪt/

- Countable Noun

- Partner in professional work, e.g. in law

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To spend time with other people; mix with

- To form a connection in your mind between things

B1TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters