Subtitles & vocabulary

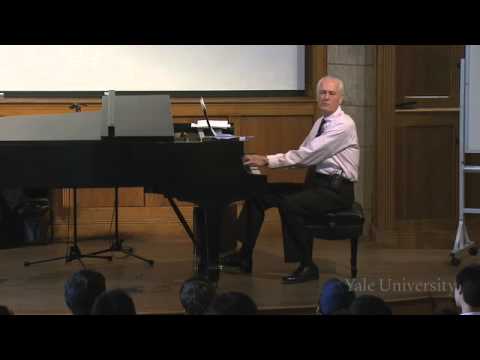

Lecture 7. Harmony: Chords and How to Build Them

00

songwen8778 posted on 2016/07/24Save

Video vocabulary

sort

US /sɔrt/

・

UK /sɔ:t/

- Transitive Verb

- To organize things by putting them into groups

- To deal with things in an organized way

- Noun

- Group or class of similar things or people

A1TOEIC

More bit

US /bɪt/

・

UK /bɪt/

- Noun

- Device put in a horse's mouth to control it

- Small piece of something

- Intransitive Verb

- (E.g. of fish) to take bait and be caught

A1

More phrase

US /frez/

・

UK /freɪz/

- Noun

- Common expression or saying

- Section of musical notes in a piece of music

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To choose words to say what you mean clearly

A2

More pattern

US /ˈpætən/

・

UK /'pætn/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Model to follow in making or doing something

- Colors or shapes which are repeated on objects

- Transitive Verb

- To copy the way something else is made

- To decorate with a pattern.

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters