Subtitles & vocabulary

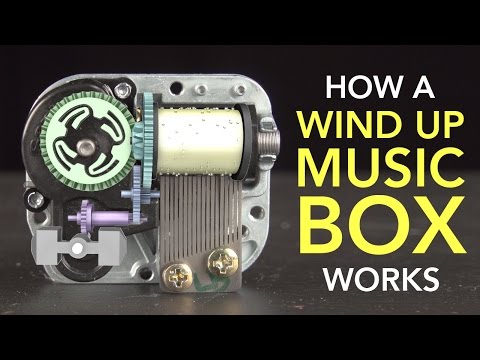

How a Wind Up Music Box Works

00

Rain posted on 2018/07/20Save

Video vocabulary

engage

US /ɪn'gedʒ/

・

UK /ɪn'ɡeɪdʒ/

- Transitive Verb

- To start to fight with an enemy

- To hire someone for a task or job

A2TOEIC

More evolve

US /ɪˈvɑlv/

・

UK /ɪ'vɒlv/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To develop certain features

- To develop or change slowly over time

B1

More strike

US /straɪk/

・

UK /straɪk/

- Transitive Verb

- To hit something

- To remove or erase.

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- A punch or hit

- Fact of not hitting the ball when playing baseball

A2TOEIC

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters