Subtitles & vocabulary

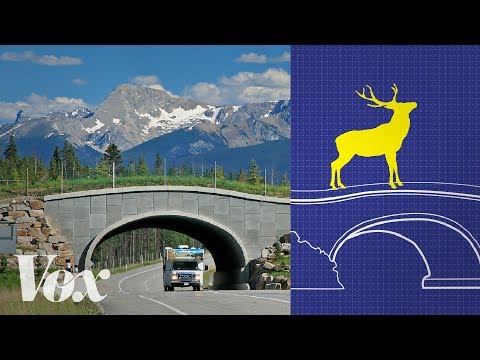

Wildlife crossings stop roadkill. Why aren't there more?

00

Boyeee posted on 2023/07/08Save

Video vocabulary

access

US /ˈæksɛs/

・

UK /'ækses/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Way to enter a place, e.g. a station or stadium

- The opportunity or right to use something or to see someone.

- Transitive Verb

- To be able to use or have permission to use

A2TOEIC

More improve

US /ɪmˈpruv/

・

UK /ɪm'pru:v/

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To make, or become, something better

A1TOEIC

More structure

US /ˈstrʌk.tʃɚ/

・

UK /ˈstrʌk.tʃə/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- The way in which the parts of a system or object are arranged or organized, or a system arranged in this way

- A building or other man-made object.

- Transitive Verb

- To plan, organize, or arrange the parts of something

A2TOEIC

More sustainable

US /səˈsteɪnəbl/

・

UK /səˈsteɪnəbl/

- Adjective

- Capable of continuing for a long time

- Able to be maintained without running out of

B2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters