Subtitles & vocabulary

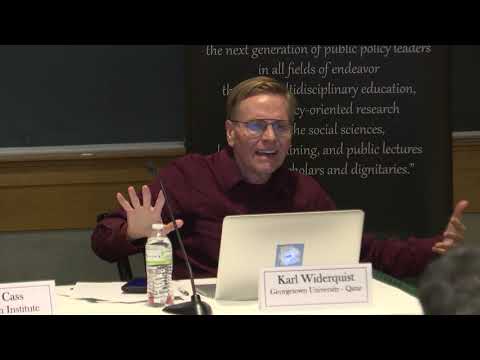

Universal Basic Income--For or Against? A Debate

00

王惟惟 posted on 2020/01/12Save

Video vocabulary

privilege

US /ˈprɪvəlɪdʒ, ˈprɪvlɪdʒ/

・

UK /'prɪvəlɪdʒ/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- Advantage or right given to only certain people

- An opportunity to do something special or enjoyable.

- Transitive Verb

- To give advantages to some people not others

B1TOEIC

More debate

US / dɪˈbet/

・

UK /dɪ'beɪt/

- Noun (Countable/Uncountable)

- General public discussion of a topic

- A formal event where two sides discuss a topic

- Verb (Transitive/Intransitive)

- To consider options before making a decision

- To take part in a formal discussion

A2TOEIC

More guarantee

US /ˌɡærənˈti/

・

UK /ˌɡærən'ti:/

- Transitive Verb

- To promise to repair a broken product

- To promise that something will happen or be done

- Countable Noun

- A promise to repair a broken product

- Promise that something will be done as expected

A2TOEIC

More negative

US /ˈnɛɡətɪv/

・

UK /'neɡətɪv/

- Noun

- The opposite to a positive electrical charge

- In grammar, containing words such as 'no' or 'not'

- Adjective

- Being harmful, unwanted or unhelpful

- In mathematics, being less than zero

A2

More Use Energy

Unlock Vocabulary

Unlock pronunciation, explanations, and filters